Praxi Data ebook

I wrote and edited a substantial ebook for AI tech startup Praxi Data, in conjunction with Phable.

I wrote and edited an expansive ebook for AI tech startup Praxi Data, in conjunction with Phable.

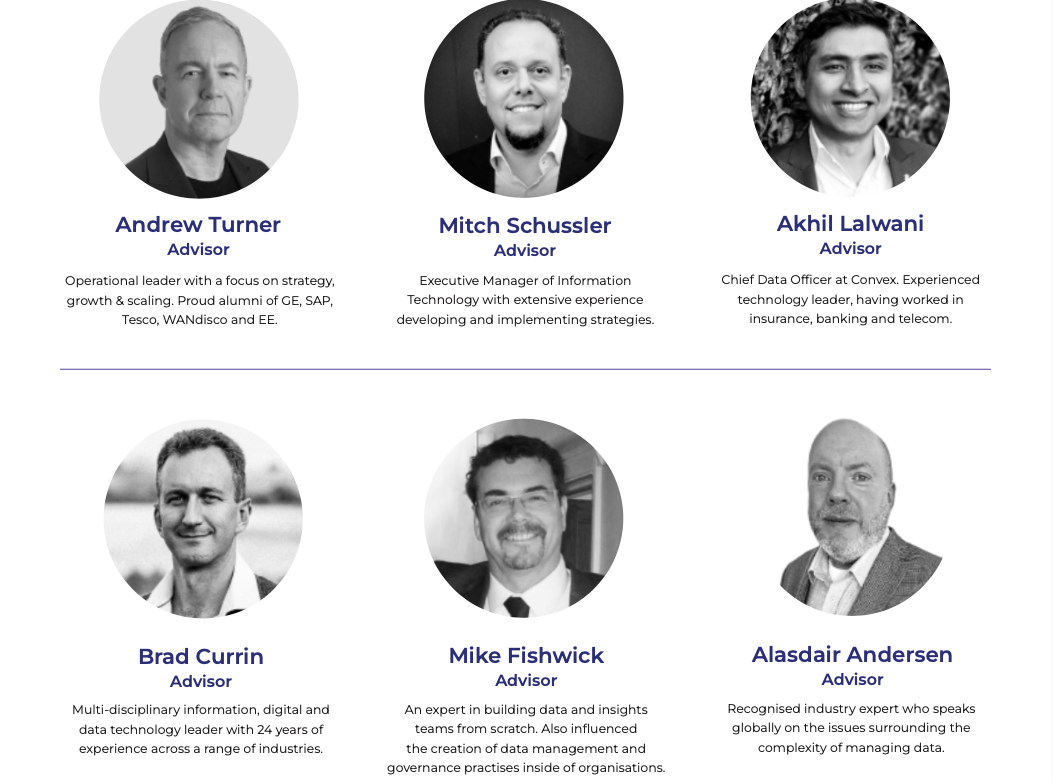

I conducted interviews with six industry experts working in senior data roles across cybersecurity, insurance, telecoms, energy and software development.

Then I brought the material together into a cohesive narrative about the power of pre-trained AI models for businesses.

The ebook was used for marketing and sales acquisition purposes by Praxi.

You can download the full ebook here.

Digital Daze

Writing and editing for this blog and magazine produced by Phable

These pieces are all from Digital Daze – a blog and beautiful printed magazine, produced by Phable.

Supply chain reaction

The disruption of the past two years has brought supply chain transparency into sharp focus. At the micro level, it has meant customers waiting weeks or months for goods to arrive. Add to this the war in Ukraine, and various industry strikes in a number of European countries, and you’ll see how things aren’t going to get any easier in the short term.

At a macro level, it has resulted in a scarcity of materials, problems in trend and financial forecasting, increasing freight prices and port congestion, and a changing of customer attitudes as they seek out other companies or routes to fulfil their requirements.

Even before the pandemic wreaked havoc, supply chains in every business sector were already hellishly complex – winding through different legal jurisdictions, technical systems, time zones and transport methods.

That complexity makes it difficult to analyse and optimise internal processes, but can also create problems with customer relationships. How can you make confident claims about your ethical and environmental standards if you can’t see the whole supply chain in granular detail?

The solutions may lie in a combination of open-source frameworks, machine learning and the blockchain. Datanomix is a tech company that applies predictive machine learning to manufacturing – providing real-time analytics data on physical processes, and allowing for continuous improvement from first component to finished product.

The Open Apparel Registry is an open-source map and database of global fashion manufacturing facilities – allowing major brands to understand exactly who they are partnering with. This enables them to assess risks with everything from sustainability to workers’ rights.

And Provenance is a social enterprise that uses the blockchain to help businesses prove to its customers exactly where their products have come from. This verified evidence can be pushed straight into marketing communications to bolster a brand’s reputation for sustainability.

Global supply chains will remain essential and fragile – new tech solutions can help make them a little more resilient and transparent.

Hackers for hire

Cybersecurity is a constant headache for companies of all sizes. Enterprises of all sizes are vulnerable to hacking – whether by state-sponsored actors, commercially driven criminal organisations, or some kid in a basement with too much time on their hands.

Intrusions can take a variety of guises, with ransomware proving particularly brutal in recent years. The Verizon Business 2022 Data Breach Investigations Report estimates that ransomware attacks have risen more in the last year than in the previous five.

Along with the range of technical precautions and behaviour change that IT teams are already deploying, there’s a human-powered approach: hackers-for-hire. There’s been a boom in tech companies providing ethical (or ‘whitehat’) hacking expertise to help enterprises understand their vulnerabilities.

HackerOne has a client list including Uber, Spotify, Twitter and Goldman Sachs. Their ‘hacker-powered security platform’ puts companies in contact with the world’s leading security experts, penetration testers and cybersecurity researchers. They coordinate bug bounty programmes – where hackers are offered rewards for finding vulnerabilities and flagging them with the company concerned, rather than hawking them on the dark web.

Alongside its technical security solutions (application scanning and surface monitoring), Detectify provides crowdsourced expertise from its global community of ethical hackers. Each time one of their whitehats finds a vulnerability, Detectify builds it into their automated scanner and makes it available to their clients.

Bugcrowd takes a similar approach. Clients define the attack surface they want to check – such as a web application front end, or a mobile or IoT platform. Bugcrowd can then push it out to the research community, or to a limited set of experts. The hackers set to work with their digital pickaxes, and share whatever chinks they find in the company armour.

When malicious hackers are the biggest threat to your business, it helps to have your own code warriors onside. As Bugcrowd founder Casey Ellis puts it: “Cybersecurity isn’t a technology problem — it’s a human one — and to compete against an army of adversaries we need an army of allies.”

Quantum leaping

The future of computing is quantum. Where classical computers convert information into ones and zeroes, quantum computers can process it as either or both. These qubits are capable of running multidimensional quantum algorithms which can tackle super-complex problems..

But while the theory is sound, quantum computing has yet to truly make the leap into real-world applications. One of the challenges is the cost of experimentation – building, adapting and maintaining the hardware to test out new ideas. Amazon Braket is attempting to make this easier, by providing cloud access to different types of quantum computers and circuit simulators to speed up research.

Another big hurdle with quantum computing has been error correction. To minimise errors in calculations, the computers need to be kept in precision-controlled, laboratory conditions – which is impractical in the longer term. Riverlane has partnered with Rigetti to tackle exactly this problem. Riverlane’s Deltaflow.OS aims to be compatible with any quantum hardware.

And Australia’s Silicon Quantum Computing achieved a major breakthrough in June 2022 by creating the world’s first quantum computer circuit – containing all of the components found in a traditional microchip, but at quantum scale. The company had already built the world’s first quantum transistor in 2012, so they’ll following the same path that led to the first classical computers.

Quantum computing is stepping out of the lab, and could be landing in your industry sooner than you think.

Radical texts

How did BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) affect the 2011 London riots? This piece originally appeared in Time Out London.

This piece originally appeared in Time Out London in August 2011.

By Monday evening, London had descended into anarchy. Fires raged across the city, looters cleaned out entire shops with impunity and riot police were pelted with missiles. The Metropolitan Police, no stranger to dealing with civil disorder, had lost control. In the midst of the chaos, flames and flying debris there were calls for the police to employ more draconian tactics to quell the violence – but this carnage was unlike anything a panicked Met had seen before. The rioters were everywhere.

Riots are unpredictable by their nature, but there’s usually some kind of geographical focus – whether it’s sustained battles around an estate or a small set of streets, the targets of vandals (banks, corporations or political institutions) or the route of a protest march. But here, although there were fierce skirmishes, the rioters didn’t seem interested in holding turf. Their tactics were hit and run: loots shops until the police turn up (even if this did sometimes take hours), or set fires and run. Countering these kind of guerrilla tactics with conventional, organised force has in war situations been likened to trying to smash a floating cork with a sledgehammer. Cordons, police lines, baton charges or kettling don’t work on people who are willing to duck away and pop up elsewhere.

In the aftermath of the riots, blame has been levelled at BlackBerry phones, and particular BBM (BlackBerry Messenger) – the seemingly benign feature that allows smartphone owners to send free messages to multiple contacts at the same time. The link between the rioters and this brand of smartphone was so specific that on Thursday Research in Motion, the Canadian manufacturer of the BlackBerry, publicly vowed to cooperate with the authorities – which could mean handing over users’ personal data and contacts to the police to help track down ringleaders. Despite this, there were calls for the BBM service to be shut down entirely, including from David Lammy, MP for Tottenham; David Cameron announced in Parliament that the government would look into curtailing access to social media for convicted rioters.

So what exactly makes BBM so different from other social networking tools, and can it really be blamed for accelerating or enabling the mass rioting?

First, some figures. Anyone who assumes that smartphones are still the preserve of wealthier grown-ups – or, in the case of the BlackBerry, high-paced business folk – hasn’t recently been in a secondary school classroom. Research published by Ofcom at the start of August found that 47% of UK teenagers own a smartphone, compared with 27% of British adults. 60% of those teens defined themselves as ‘addicted’ to the device, and 71% had their device switched on all the time. 37% of smartphone-owning teens are carrying a BlackBerry, compared with 17% for the iPhone. As far as market penetration goes, those figures are frankly astonishing.

BBM is an instant messaging application that comes pre-installed on many Blackberry handsets. It allows the owner to rapidly send and receive messages to other BlackBerry devices using the mobile phone network, or WiFi. Messages can be exchanged with multiple recipients at once, and are encrypted and thus only visible to the contacts involved – invited contacts who also have BlackBerrys. Each person on BBM becomes a node – a connection point on the network linked to many others.

Networked communications can be hugely advantageous in violent and fast-moving environments. When the Nazis launched the initial assaults that become World War 2, the speed and aggression of their tactics – particularly using tanks – led to them being dubbed blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) by Western journalists. This has led to a misconception that the German tanks were somehow quicker, or otherwise superior. In fact, as social media commentator Clay Shirky points out in his 2008 book ‘Here Comes Everybody’, the Allied tanks were superior to the Nazi machines in almost every respect – apart from one. The German tanks were fitting with radios, which allowed them not only to communicate with their commanders, but also each other. The speed of the German attacks wasn’t about physical pace – it was down to the efficiency of their communication network.

On a purely tactical level, rioters using BBM would have same advantages. There was no centralised control. Instructions or calls to action could be sent out, and the most compelling would be passed on and be more likely to be followed. Since there is no hierarchy through which orders are passed down, the network is robust – the loss of one node (if a rioter was arrested) will not cause it to collapse.

By contrast, the Met operate with a centralised leadership and top-down control. Police on the ground can and do make tactical decisions according to what they’re encountering, but significant orders must be filtered down from above (particularly about where to deploy officers), by a command structure that’s in turn relying on information about what’s happening at street level to filter back up. It’s a system that makes for orderly, accountable decisions – but compared to the headless network, it’s slow.

But just because BBM could have given the rioters and advantage over the police, it doesn’t mean it did. Young Londoners don’t need complicated communications strategies to see or hear Met riot police coming (sirens and helicopters are more than sufficient), and the rolling Sky News and BBC coverage provided plenty of information on where the latest flashpoints were. Indeed it was the dramatic TV images that demonstrated how easy it was to loot shops, and how hideously spectacular arson can be.

Also, BBM certainly wasn’t the only type of communication used by the rioters to choose their next targets – and if the BlackBerry network was shut down, they certainly would have found another way to distribute messages. Any decision to close the BBM network would be highly controversial among civil liberties campaigners, who point out that social networking sites have provided a way for protestors in the Middle East to fight and overthrow dictatorial governments. In cases where the distinction between ‘riot’ and ‘protest’ are less clear cut than recent events, it becomes worrying to imagine the authorities over here shutting down communication networks to try and maintain the status quo.

Communications technology may have increased the efficiency and co-ordination of some of last week’s rioters – but to blame it for the violence itself is to evade the bigger issues. BBM and social media are neither inherently good nor inherently bad – they are what people use them for. The technology employed by the participants in the riots will tell us nothing about the motives of the rioters, or the complex factors that led to destruction on such a mass scale.

And maybe it’s just easier for us to accept the idea that such mass carnage was organised and directed, through BBM or anything else, than it is to countenance the alternative: that huge numbers of disaffected youths, in London and across the UK, spontaneously joined in with a spree of looting and arson because they simply have no vested interest in society.

That’s an uncomfortable message to receive.

Image above by Connor Danylenko.

Human companies

Technology dominates discussions about the future of work, but businesses may be judged far more harshly on how they treat their people

Technology dominates discussions about the future of work, but businesses may be judged far more harshly on how they treat their people.

Over the past few years, a string of legal actions, online campaigns, journalistic investigations and pushes for regulation on the part of government would seem to suggest that the ‘people’ aren’t happy with the manner in which companies behave towards humans when left to their own devices. The real question now is whether this dissatisfaction is going to change anything. And if so, how much?

Your business dashboard is broken (here's how to fix it)

Business dashboards are everywhere. Most of them are awful. Based on years of experience working with hundreds of different organisations, here's my take on what goes wrong with this form of data visualisation – and how to improve it

Business dashboards are everywhere. Most of them are awful.

I know this, because I’ve spent much of last four years delivering data visualisation training for a whole range of different organisations – government departments, health institutions, big corporations, growing startups, and charities. None of them have any shortage of data – all of them face challenges in finding meaningful ways to present it.

5 reasons your data presentation isn’t working

Data is the lifeblood of modern businesses – but it only becomes truly valuable when you can transmit the meaning to others. I run data visualisation training for startups, corporates, public sector organisations and charities. Here are the five most common mistakes I’ve found people make when presenting data.

Data is the lifeblood of modern businesses – but it only becomes truly valuable when you can transmit the meaning to others. I run data visualisation training for startups, corporates, public sector organisations and charities. Here are the five most common mistakes I’ve found people make when presenting data.

The blackmail algorithm

The Ashley Madison hack was just one example of our vulnerability to hackers. I looked at the techniques and technology being used to access your personal data.

The Ashley Madison hack was just one example of our vulnerability to hackers. I looked at the techniques and technology being used to access your personal data.

Police, camera, action

In May 2014, the Metropolitan Police in London fitted 500 officers with body cameras. The news was greeted with little fanfare but, it could represent a potentially momentous shift in our relationship with the law

In May 2014, the Metropolitan Police in London fitted 500 officers with body cameras. The news was greeted with little fanfare but, it could represent a potentially momentous shift in our relationship with the law.

Mexican standoff

On 15th July 2013, the leader of the most brutal drug cartel in Mexico was finally arrested. Until the Mexican police took him in, only one enemy had ever truly defeated him – the shadowy super-geeks of Anonymous.

On 15th July 2013, the leader of the most brutal drug cartel in Mexico was finally arrested. Until the Mexican police took him in, only one enemy had ever truly defeated him – the shadowy super-geeks of Anonymous.

Your p@55word has expired

The most widespread and oldest form of digital security is fundamentally broken – we just haven’t accepted it yet. I took a look at just how vulnerable we are, and what the alternatives might be

The most widespread and oldest form of digital security is fundamentally broken – we just haven’t accepted it yet. I took a look at just how vulnerable we are, and what the alternatives might be.

Weapons of mass production

Could 3D printers be used to create cheap, untraceable guns that anyone with an internet connection could manufacture at home? As Defence Distributed launched its campaign to build a universal Wiki Weapon, I investigated how Bre Pettis and his Replicator machine are set to revolutionise the world of manufacturing, ushering in an era of DIY Nikes and printout pistols

Could 3D printers be used to create cheap, untraceable guns that anyone with an internet connection could manufacture at home? As Defence Distributed launched its campaign to build a universal Wiki Weapon, I investigated how Bre Pettis and his Replicator machine are set to revolutionise the world of manufacturing, ushering in an era of DIY Nikes and printout pistols.

Read the piece on Delayed Gratification.

Breaking bad

As internet news outlets race to be first to a story, some of them are going a little too fast – attempting to pre-empt court verdicts, sports results and notable deaths.

As internet news outlets race to be first to a story, some of them are going a little too fast – attempting to pre-empt court verdicts, sports results and notable deaths.

Read the piece on Delayed Gratification.

Planking and the contagiousness of culture

When the strange global trend for ’planking’ claimed its first victim, I took a look at meme theory and asks whether it can explain the sometimes fatal desire to impersonate a piece of wood

When the strange global trend for ’planking’ claimed its first victim, I took a look at meme theory and asks whether it can explain the sometimes fatal desire to impersonate a piece of wood.

The panda problem

Two of the star attractions at Edinburgh Zoo – giant pandas Tian Tian and Yang Guang – arrived in December 2011 following a £6 million deal struck with the Chinese government in January of that year. But can we afford to keep these layabout animals – and how do we justify the cost of propping up a species that doesn’t appear to want to be saved?

Two of the star attractions at Edinburgh Zoo – giant pandas Tian Tian and Yang Guang – arrived in December 2011 following a £6 million deal struck with the Chinese government in January of that year. But can we afford to keep these layabout animals – and how do we justify the cost of propping up a species that doesn’t appear to want to be saved?